I have a tendency to get intimidated by intellectual, long-form essays and philosophical arguments. I am still too scared to use the phrase “intersectionality” in conversation for fear I’ll somehow Yogi Berra it. Maybe it’s the communications degree tucked in my desk drawer that keeps me humble. Maybe it’s my midwestern humility. But the idea of discussing how the world works in can sometimes feel above my pay grade. That’s not to say my conversations top out at Tristan Thompson-Khloe Kardashian drama, but I don’t want to bring a knife to a gun fight, y’know?

But! Something I automatically understood when reading about it was the concept of the “female gaze,” a term that came to prominence in the past few years, and which I happily talk about with everyone I know.

This feminist film term sprang up to challenge an earlier intellectual concept that’s (still) seen as the cultural default: “the male gaze.” The British film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the male gaze term in 1975 to point out that so much of what we consume in culture is art created by and for men. The male gaze represents not only the “gaze” of the male viewer, but also that of the film’s (usually) male protagonist and its (usually) male director or creator.

The female gaze, then, is about female creators, female protagonists, and the female audiences consuming that art.

Before you tune out and assume that calling attention to the male gaze is a way to call out male directors, writers, and musicians for objectifying women—Not all characters are Megan Fox in Transformers! I get it—and that therefore anything created with a female gaze is just going to be a female protagonist telling her dumb-but-hot boyfriend to take his shirt off, stick with me.

Pointing out the existence of the male gaze is actually a way to explain that a male view is simply a limited view, especially when the rest of the characters exist mainly to serve him and his interests, and to tell his story. Think Claire Foy in First Man, whose character seemed there only to speak Ryan Gosling’s character’s emotions out loud for him. If a movie had been centered around her experience, we would have gotten a whole different perspective (and honestly, probably a lot less staring at the moon scenes).

The male gaze, much like white privilege, is mostly invisible to those who benefit from it. Privilege is the absence of cultural impediments to success. Privilege doesn’t catapult you to the finish line, but acknowledging it is to accept that your starting point may be different from others’ starting point, and that this difference has consequences in your respective races.

Similarly, it’s worth acknowledging that so much of the art we consume has presented itself to us as not one specific lens through which to view the world, but how the world, in fact, is.

If art—whether music, movies, or books—more easily syncs up with your understanding of the world (the world you can see between the blinders you’re wearing, if you will), it’s easy to think it’s because that’s the whole world. The result is that you miss out on expanding your understanding of different viewpoints. You miss out, in fact, on the whole world.

And that’s where things get fucked up. No one wants to ban men from making movies (except Peter Farrelly! Someone take his camera away!) or music or art, or comedy, but the art they make approaches propaganda when they’re the only ones given the opportunity.

To make an absurd but hopefully helpful analogy, if only cats had ever written and directed movies, we’d think all dogs were pretty much the worst. It wouldn’t be until dogs started making movies that we’d get a different lens through which to view both dogs and cats. But it’d be pretty tough to start trusting dogs to make movies because a) the stories we’d consumed would have made us think they’re not up to the task, and b) only cats had made successful movies (conveniently forgetting that plenty of cat writers and directors had made huge flops), so it would seem like a risk to let a dog make a movie.

So, what is the female gaze and how does it help us in understanding women better?

Put simply, the female gaze describes art being created via the viewpoint of a woman, with a female audience in mind.

My cats and dogs analogy above is, unfortunately, not too far off. Male directors have historically been the ones to make movies because men have historically dominated the work force—those movies make money (though of course, plenty don’t), leading the studio execs to believe correlation implies causation. They see the formula as: male director + movie = box office success. And often not just male director, but male screenwriter, adapting a screenplay from a male-authored book, and on and on.

What gets lost when women don’t get to tell their stories is a deeper understanding of women.

While I feel confident that by now I know quite well how white middle class american men think about (thanks, though, Esquire)…well, quite a lot of things, I don’t think the same can be said in reverse.

When you suddenly find you are not the default, it makes you re-examine a lot of things. Well, hopefully. Because right now the last thing we need is to reinforce the notion that being (white and) male is the standard way to be human.

So! Our team compiled a list of art created by women that would immediately enrich your life precisely because they offer viewpoints you may not have heard while chatting with your pals in a subreddit about the next Avengers movie. It’s mostly recent stuff, because I am a millennial who would pretty happily burn anything to the ground made before 1990 (kidding, mostly). Obviously feel free to reach back farther in your own journey into the female gaze, which I trust all of you will be after reading this.

Below, what to read, watch, and listen to for a better understanding of women:

What to watch to better understand women

Wonder Woman

SG Says: I’m not here to get into a fight about the merits of Hawkeye’s superhero powers, but what I will say is that it’s hard to see yourself as a superhero without literally seeing yourself as a superhero. In the hands of a male director and not Patty Jenkins, how much do you want to bet we would have seen way more jiggling boobs from the warriors in slow-motion running shots in Wonder Woman? I’m guessing at least 500% more jiggle.

That’s a rough estimate but most likely correct.

Ali Wong Netflix specials

SG Says: She’s pregnant, and she’s funny. Who knew! Ali Wong has now filmed two Netflix stand-up specials, Hard Knock Wife and Baby Cobra with a child about to come out of her “wherever” (as the president calls the vagina). They’re both hilarious.

Sex & The City

SG Says: The OG female gaze (okay, okay, not the OG but again, we’re only going back to the ’90s!). If you’ve watched, then you know. So much of our conversations about dating and relationships can be explained with a comparison to Carrie Bradshaw and her brunch companions. We know what it means to be dating a Big because of SATC. If you haven’t watched by now, it’s basically like not speaking a language everyone else already understands. Learn to code! Except in this case, ‘code’ just means binging every episode and realizing you’re definitely a Miranda.

To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before

SG Says: Black Panther did so well because black moviegoers were excited to see themselves as superheroes, and Ryan Coogler was uniquely situated to direct such a film. Crazy Rich Asians was embraced by an Asian audience, a film with a majority asian cast, an asian director, and pulled from a wildly successful asian-american penned novel. To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, a YA novel by Jenny Han-turned-Netflix romcom, stars a female teenage Asian-American protagonist, which…think hard, you really haven’t seen before. ‘Til now. Get to watching.

The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt

SG Says: This show, from the mind of Tina Fey is great, and it’s all over! So you can binge the whole thing on Netflix in a weekend. “Earnest” is not usually a term that describes great comedy but The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt will change your mind.

What to read to better understand women

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger by Rebecca Traister

SG Says: Want to know why women are so angry? If you don’t already, that doesn’t bode well for you, buddy, but all the more reason to pick up Traister’s book so it’ll soon become clear.

Prep by Curtis Sittenfeld

SG Says: Reading books by and about women is a good reminder that the interior lives of female protagonists are just as interesting as men’s and that you don’t have to inject international intrigue or mysterious murders to write a total page-turner.

Everything’s Trash But It’s Okay by Phoebe Robinson

SG Says: Good news, you can also listen to the multi-talented Robinson on Two Dope Queens, her podcast with Jessica Williams and watch her HBO special with Williams, under the same name (the hair episode from season 1 is a particular favorite).

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

SG Says: Ayy, this came out before the 1990s! I did it!

*Okay, the book not the movie, but it counts.

What to listen to to better understand women

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, Lauryn Hill

SG Says: A legend, full-stop.

Jagged Little Pill, Alanis Morissette

SG Says: My best friend in the world, were she ever to be elected to public office, would most likely swear to uphold the duties on a copy of Alanis Morissette’s crazy-iconic Jagged Little Pill. This album is her bible, and after a few recent listens, I better understand why. It’s angry without rejecting empathy, a tight wire balance only great singer-songwriters can achieve.

“Juice” by Lizzo

SG Says: The talented musician, who identifies as queer, makes music for living out your own personal makeover montage. Put “Juice” on repeat and see if you don’t step out of the house a newer, better, brighter person.

Golden Hour, Kacey Musgraves

SG Says: Album of the year! By a country singer! Praise be.

What to look at to better understand women

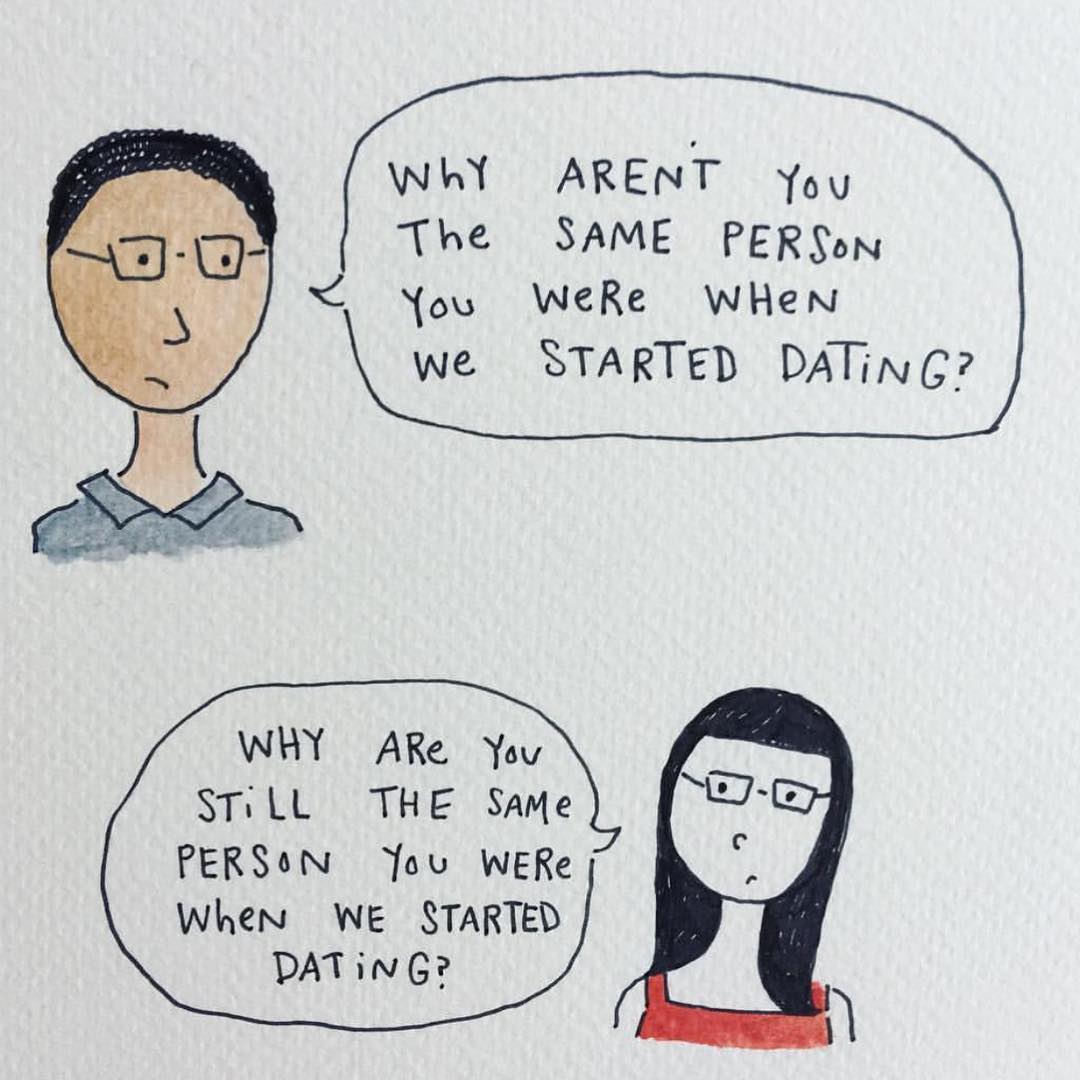

Mari Andrew’s Instagram

SG Says: How the artist and now author gets into women’s minds so well, it seems she’s lived a thousand lives, and half of them were mine.

Girl Gaze

SG Says: Photographer and activist Amanda de Cadanet started this creative agency/tech company to connect brands with the global community of female creatives. Their mission is to close the gender gap by supporting Gen Z and Millennial creative females by providing paid job opportunities. This is their Instgram.

TELL ME:

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT THE CONCEPT OF THE FEMALE GAZE VS. THE MALE GAZE?